Mortality

Around the globe

The Spanish flu infected around 500 million people, about one-third of the world's population. Estimates as to how many infected people died vary greatly, but the flu is regardless considered to be one of the deadliest pandemics in history. An early estimate from 1927 put global mortality at 21.6 million. An estimate from 1991 states that the virus killed between 25 and 39 million people. A 2005 estimate put the death toll at 50 million (about 3% of the global population), and possibly as high as 100 million (more than 5%). However, a 2018 reassessment in the American Journal of Epidemiology estimated the total to be about 17 million, though this has been contested. With a world population of 1.8 to 1.9 billion, these estimates correspond to between 1 and 6 percent of the population.

A 2009 study in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses based on data from fourteen European countries estimated a total of 2.64 million excess deaths in Europe attributable to the Spanish flu during the major 1918–1919 phase of the pandemic, in line with the three prior studies from 1991, 2002, and 2006 that calculated a European death toll of between 2 million and 2.3 million. This represents a mortality rate of about 1.1% of the European population (c. 250 million in 1918), considerably higher than the mortality rate in the U.S., which the authors hypothesize is likely due to the severe effects of the war in Europe. The excess mortality rate in the U.K. has been estimated at 0.28%-0.4%, far below this European average.

Some 12–17 million people died in India, about 5% of the population. The death toll in India's British-ruled districts was 13.88 million. Another estimate gives at least 12 million dead. The decade between 1911 and 1921 was the only census period in which India's population fell, mostly due to devastation of the Spanish flu pandemic. While India is generally described as the country most severely affected by the Spanish flu, at least one study argues that other factors may partially account for the very high excess mortality rates observed in 1918, citing unusually high 1917 mortality and wide regional variation (ranging from 0.47% to 6.66%). A 2006 study in The Lancet also noted that Indian provinces had excess mortality rates ranging from 2.1% to 7.8%, stating: "Commentators at the time attributed this huge variation to differences in nutritional status and diurnal fluctuations in temperature."

In Finland, 20,000 died out of 210,000 infected. In Sweden, 34,000 died.

In Japan, 23 million people were affected, with at least 390,000 reported deaths. In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died among 30 million inhabitants. In Tahiti, 13% of the population died during one month. Similarly, in Western Samoa 22% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.

In Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Empire, 6,403 to 10,000 died, giving the city a mortality rate of at least 0,56%.

In New Zealand, the flu killed an estimated 6,400 Pakeha and 2,500 indigenous Maori in six weeks, with Māori dying at eight times the rate of Pakeha.

In the U.S., about 28% of the population of 105 million became infected, and 500,000 to 850,000 died (0.48 to 0.81 percent of the population). Native American tribes were particularly hard hit. In the Four Corners area, there were 3,293 registered deaths among Native Americans. Entire Inuit and Alaskan Native village communities died in Alaska. In Canada, 50,000 died.

In Brazil, 300,000 died, including president Rodrigues Alves.

In Britain, as many as 250,000 died; in France, more than 400,000.

In Ghana, the influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people. Tafari Makonnen (the future Haile Selassie, Emperor of Ethiopia) was one of the first Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived. Many of his subjects did not; estimates for fatalities in the capital city, Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher.

The death toll in Russia has been estimated at 450,000, though the epidemiologists who suggested this number called it a "shot in the dark". If it is correct, Russia lost roughly 0.4% of its population, meaning it suffered the lowest influenza-related mortality in Europe. Another study considers this number unlikely, given that the country was in the grip of a civil war, and the infrastructure of daily life had broken down; the study suggests that Russia's death toll was closer to 2%, or 2.7 million people.

Devastated communities

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many adults were incapacitated that much of everyday life was hampered. Some communities closed all stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There were reports that healthcare workers could not tend the sick nor the gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.

Bristol Bay, a region of Alaska populated by indigenous people, suffered a death rate of 40 percent of the total population, with some villages entirely disappearing.

Several Pacific island territories were hit particularly hard. The pandemic reached them from New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent ships, such as the SS Talune, carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand, the flu reached Tonga (killing 8% of the population), Nauru (16%), and Fiji (5%, 9,000 people). Worst affected was Western Samoa, formerly German Samoa, which had been occupied by New Zealand in 1914. 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women, and 10% of children died. By contrast, Governor John Martin Poyer prevented the flu from reaching neighboring American Samoa by imposing a blockade. The disease spread fastest through the higher social classes among the indigenous peoples, because of the custom of gathering oral tradition from chiefs on their deathbeds; many community elders were infected through this process.

In Iran, the mortality was very high: according to an estimate, between 902,400 and 2,431,000, or 8% to 22% of the total population died. The country was going through the Persian famine of 1917–1919 concurrently.

In Ireland, during the worst 12 months, the Spanish flu accounted for one-third of all deaths.

In South Africa it is estimated that about 300,000 people amounting to 6% of the population died within six weeks. Government actions in the early stages of the virus' arrival in the country in September 1918 are believed to have unintentionally accelerated its spread throughout the country. Almost a quarter of the working population of Kimberley, consisting of workers in the diamond mines, died. In British Somaliland, one official estimated that 7% of the native population died. This huge death toll resulted from an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.

Less-affected areas

In the Pacific, American Samoa and the French colony of New Caledonia also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines. Australia also managed to avoid the first two waves with a quarantine. Iceland protected a third of its population from exposure by blocking the main road of the island. By the end of the pandemic, the isolated island of Marajó, in Brazil's Amazon River Delta had not reported an outbreak. Saint Helena also reported no deaths.

Estimates for the death toll in China have varied widely, a range which reflects the lack of centralized collection of health data at the time due to the Warlord period. China may have experienced a relatively mild flu season in 1918 compared to other areas of the world. However, some reports from its interior suggest that mortality rates from influenza were perhaps higher in at least a few locations in China in 1918. At the very least, there is little evidence that China as a whole was seriously affected by the flu compared to other countries in the world.

The first estimate of the Chinese death toll was made in 1991 by Patterson and Pyle, which estimated a toll of between 5 and 9 million. However, this 1991 study was criticized by later studies due to flawed methodology, and newer studies have published estimates of a far lower mortality rate in China. For instance, Iijima in 1998 estimates the death toll in China to be between 1 and 1.28 million based on data available from Chinese port cities. The lower estimates of the Chinese death toll are based on the low mortality rates that were found in Chinese port cities (for example, Hong Kong) and on the assumption that poor communications prevented the flu from penetrating the interior of China. However, some contemporary newspaper and post office reports, as well as reports from missionary doctors, suggest that the flu did penetrate the Chinese interior and that influenza was severe in at least some locations in the countryside of China.

Although medical records from China's interior are lacking, extensive medical data was recorded in Chinese port cities, such as then British-controlled Hong Kong, Canton, Peking, Harbin and Shanghai. This data was collected by the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, which was largely staffed by non-Chinese foreigners, such as the British, French, and other European colonial officials in China. As a whole, accurate data from China's port cities show astonishingly low mortality rates compared to other cities in Asia. For example, the British authorities at Hong Kong and Canton reported a mortality rate from influenza at a rate of 0.25% and 0.32%, much lower than the reported mortality rate of other cities in Asia, such as Calcutta or Bombay, where influenza was much more devastating. Similarly, in the city of Shanghai – which had a population of over 2 million in 1918 – there were only 266 recorded deaths from influenza among the Chinese population in 1918. If extrapolated from the extensive data recorded from Chinese cities, the suggested mortality rate from influenza in China as a whole in 1918 was likely lower than 1% – much lower than the world average (which was around 3–5%). In contrast, Japan and Taiwan had reported a mortality rate from influenza around 0.45% and 0.69% respectively, higher than the mortality rate collected from data in Chinese port cities, such as Hong Kong (0.25%), Canton (0.32%), and Shanghai.

Patterns of fatality

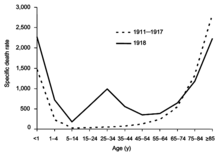

The pandemic mostly killed young adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of pandemic influenza deaths in the U.S. occurred in people under 65, and nearly half of deaths were in young adults 20 to 40 years old. In 1920, the mortality rate among people under 65 had decreased sixfold to half the mortality rate of people over 65, but 92% of deaths still occurred in people under 65. This is unusual since influenza is typically most deadly to weak individuals, such as infants under age two, adults over age 70, and the immunocompromised. In 1918, older adults may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the 1889–1890 flu pandemic, known as the "Russian flu". According to historian John M. Barry, the most vulnerable of all – "those most likely, of the most likely", to die – were pregnant women. He reported that in thirteen studies of hospitalized women in the pandemic, the death rate ranged from 23% to 71%. Of the pregnant women who survived childbirth, over one-quarter (26%) lost the child.Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.

There were also geographic patterns to the disease's fatality. Some parts of Asia had 30 times higher death rates than some parts of Europe, and generally, Africa and Asia had higher rates, while Europe, North America, and Asia had lower ones. There was also great variation within continents, with three times higher mortality in Hungary and Spain compared to Denmark, two to three times higher chance of death in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to North Africa, and possibly up to ten times higher rates between the extremes of Asia. Cities were affected worse than rural areas. There were also differences between cities, which might have reflected exposure to the milder first wave giving immunity, as well as the introduction of social distancing measures.

Another major pattern was the differences between social classes. In Oslo, death rates were inversely correlated with apartment size, as the poorer people living in smaller apartments died at a higher rate. Social status was also reflected in the higher mortality among immigrant communities, with Italian Americans, a recently arrived group at the time, were nearly twice as likely to die compared to the average Americans. These disparities reflected worse diets, crowded living conditions, and problems accessing healthcare. Paradoxically, however, African Americans were relatively spared by the pandemic.

More men than women were killed by the flu, as they were more likely to go out and be exposed, while women would tend to stay at home. For the same reason men also were more likely to have pre-existing tuberculosis, which severely worsened the chances of recovery. However, in India the opposite was true, potentially because Indian women were neglected with poorer nutrition, and were expected to care for the sick.

A study conducted by He et al. (2011) used a mechanistic modeling approach to study the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. They examined the factors that underlie variability in temporal patterns and their correlation to patterns of mortality and morbidity. Their analysis suggests that temporal variations in transmission rate provide the best explanation, and the variation in transmission required to generate these three waves is within biologically plausible values. Another study by He et al. (2013) used a simple epidemic model incorporating three factors to infer the cause of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. These factors were school opening and closing, temperature changes throughout the outbreak, and human behavioral changes in response to the outbreak. Their modeling results showed that all three factors are important, but human behavioral responses showed the most significant effects.

Comments

Post a Comment